“[The] right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” – Justice Harry Blackmun

“[The] right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” – Justice Harry Blackmun

Those words shook America back in 1973 and the Constitutional right to privacy was born. I don’t want to dwell on the pro- or anti-abortion position in this article, but I do want to look at how the Supreme Court came up with the right to privacy. It’s a fascinating study of how the Court can create legal standards even though the Constitution says all legislative power is vested in Congress.

The idea of judicial review is part of English Common Law, but it’s not used to set aside laws in that country unless they conflict with a treaty. When Justice Marshall asserted it for the Supreme Court in Marbury v. Madison, he created a new form of judicial review, in which courts could essentially exercise veto power over a law if they could craft a Constitutional argument to justify it. Never mind that some of the nation’s founding fathers spoke out against the idea of judicial review: Justice Marshall not only brought it into American law, he made it into something more powerful that it had been anywhere in the world, before or since.

Since Marshall’s assertion of power, the Court has been able to do some incredible things to American politics, not all of them constructive. The Supreme Court has produced some decisions that critics derided as bad law based upon bad reasoning. Bad as those decisions may be, they were those of the Supreme Court and they stand. In the case of Roe, the amazing creation of the right to privacy stunned many observers and led to further discussion of what, exactly the Supreme Court should be able to do. Discussion could not change the fact that the Supreme Court could pretty much do whatever it wanted to do, so long as it made up a reason to do it. H.L. Mencken once quipped that a judge is a law school student that gets to grade his own papers. In the case of the Supreme Court, there’s no appeal to how the student got his grade: it’s always an A+.

While it’s true that just as the Supreme Court can craft stupid rulings, Congress can pass stupid laws. Those laws of Congress, however, are at least closer to the people who they ultimately have to answer to. The Supreme Court answers to no one, as Thomas Jefferson pointed out: “Their power [is] the more dangerous as they are in office for life, and not responsible, as the other functionaries are, to the elective control.”

(NOTE: This is *not* about abortion. This is about judicial review and how it can produce interesting results. Please keep your comments focused on judicial review.)

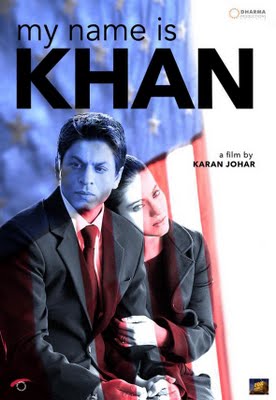

The film comes out Friday, February 12th, but I’m thinking of seeing it either on a Saturday or a Wednesday. Tickets are 2-for-1 on Wednesday and only $5.00 for matinee showtimes on Saturday. THIS WILL BE FOR CLASS PARTICIPATION POINTS, IF YOU WANT THEM!!! It’s not required, but this does look to be an awesome film. One aspect of the film deals with life in America post 9-11 for Muslims, but there’s much more to it than just that.

The film comes out Friday, February 12th, but I’m thinking of seeing it either on a Saturday or a Wednesday. Tickets are 2-for-1 on Wednesday and only $5.00 for matinee showtimes on Saturday. THIS WILL BE FOR CLASS PARTICIPATION POINTS, IF YOU WANT THEM!!! It’s not required, but this does look to be an awesome film. One aspect of the film deals with life in America post 9-11 for Muslims, but there’s much more to it than just that. “[The] right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” – Justice Harry Blackmun

“[The] right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment’s reservation of rights to the people, is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” – Justice Harry Blackmun